Reviving The Lost Art of Movie Novelizations with Mike Sacks

Parodying cult films of the past has never been more fun.

By Doug Rapp

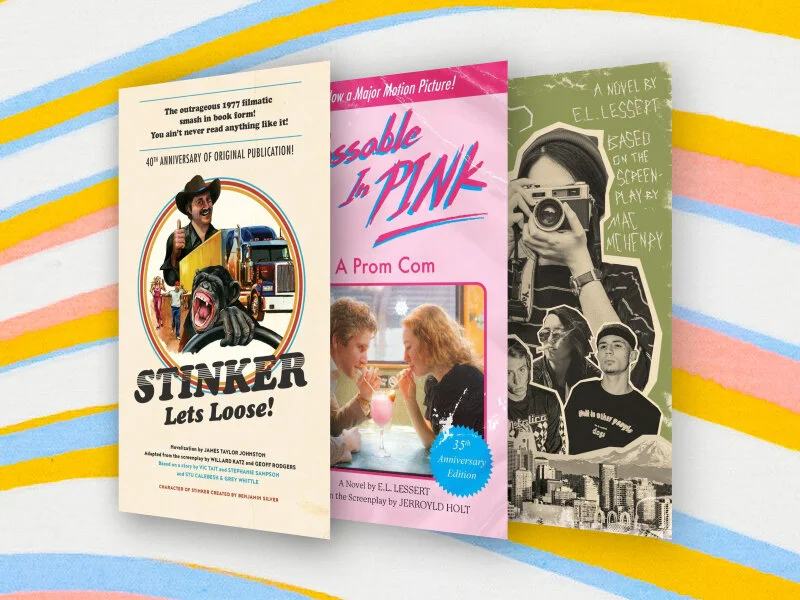

These book titles by Mike Sacks might sound familiar, but there’s always a twist.

In ye olden days before the internet, a movie hit the local big screen, stayed there for a number of weeks depending on its popularity, then disappeared until it resurfaced months or years later on television or in video stores.

Back then, studios and publishers sensed an opportunity to cash in on restless fans waiting to relive their favorite stories. Using mostly unknown, low-paid writers who could generate copy quickly, these companies produced movie novelizations. Essentially printed-word versions of hit movies, these “movie books” usually coincided with a film’s release and were sold to voracious viewers wanting to relive what they’d just seen.

Movie novelizations basically recreate a movie — just in prose form. They differ from a simple screenplay by digging into characters’ thoughts and backstories more than dialogue and action can.

Sometimes, movie novelizations embellish or even add origin-story details, as in the case of the novelization of Gremlins (in which the Mogwai are eloquent aliens). Sometimes, the novelizations take a left turn, adding weird sexual subplots, as happened in the novelization of E.T. (Spoiler: E.T. totally wants to bed Elliot’s single mom.)

These days, movie novelizations are mostly a pop culture relic since films can be seen online before they’re even released, and scripts are easily accessible, too.

But there are some writers, like Mike Sacks, who are trying to keep this largely lost art alive. In his free time, Sacks, an editor at Vanity Fair, has penned three movie novelizations that both satirize and take inspiration from popular films of the recent past. So far, Sacks’ novelizations have skewered the macho sexism and casual racism of drive-in movies from the 1970s, the preppy banality of 1980s movies, and the affected ennui of 1990s fare. He writes his novelizations intentionally using the same passably competent prose of these old movie tie-ins, which he avidly collects.

His latest movie book, Slouchers — clearly a take on Gen X movies such as Reality Bites and Singles — looks at grungified life in Seattle in the early ’90s. Previously, he parodied the Molly Ringwald-starring cult classic Pretty in Pink with his own version of it, Passable in Pink. And he based Stinker Lets Loose, a ’70s car-chase-and-orangutan action-comedy, on Smokey and the Bandit and similar films from that era.

“I started [buying novelizations] as a kid,” Sacks said.

“My first novelization was Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. I loved these books. The reason I loved them was because back then, in the ’80s, one could not re-live movies via the internet or with cable or in any other way. You saw a movie and then it disappeared from your life for a long time. The only way for me to re-experience the movies that I loved was through the page, through novelizations.”

Sacks’ movie books are carrying on a niche of publishing that’s mostly died out. Gone are the days when a checkout lane would be lined with copies of Gremlins or Jaws 2 novelizations.

“[Novelizations] are just not needed,” Sacks said. “We can see movies in our homes the day they are released and we can keep seeing them. We can then check out interviews on the internet with the film’s actors and we can immediately download the soundtrack. We can even download the script! That’s pretty amazing. We don’t have to live vicariously through novelizations anymore.”

Sacks said he also likes how movie novelizations can have different storylines and endings since they’re often based on early drafts of the script.

“For instance, in the movie Pretty in Pink, the Molly Ringwald character, Andie Walsh, ends up with Blane,” he said of the 1986 John Hughes classic. “I found that reprehensible. In the novelization, Andie ends up with Ducky, which was the original story. Now this isn’t exactly up there with discovering the authentic Hitler diaries, but as a kid I found all this amazing. There was very little stimuli in the ’80s for a suburban kid. I found escape through these books. Also sports. And alcohol. And sex with myself. I still do.”

Behold: A photo of Sacks lobbing an empty Miller Lite can at a camera. (Mike Sacks)

Comedy writing has always been a focus for the Virginia native who graduated from Tulane in New Orleans in 1995 with an English literature degree. He’s written for Funny or Die, MAD, McSweeney’s, and VICE, and has published two collections of interviews with comedy greats, such as Harold Ramis, Bob Odenkirk, Merrill Markoe, and Megan Amran.

“He’s the best kind of comedy writer,” Andy Richter once blurbed about Sacks, “a bona fide weirdo with virtually no interest in satisfying anything other than his own personal obsessions.”

Sacks said he turned his attention to movie books a few years ago because it was a fun way to write his own films.

“In essence, these are all complete little movie productions, all neatly packaged. They’re also Trojan horses. I can smuggle in satirical elements of each of these fake movies, as well as satirical elements about the times in which they were produced.”

“I also wanted to publish a new book that looked old, a book that appeared as if it had been sitting in the back of a flea market for years,” he added.

Flea markets, incidentally, are where Sacks finds the outsider books and art that he enjoys most.

“I love stores and places where you can find objects that you wouldn’t be able to find anywhere else in the world,” Sacks said. “Stores like Barnes & Noble bore me to tears. I just don’t find it interesting. You’re going to find the same books in a Barnes & Nobles in Alaska as you would inside a Barnes & Nobles in Louisiana.

“I love used bookstores, used record stores, flea markets, garage sales, all that. I love to discover books and records and art that I couldn’t find anywhere else in the world. I just love shit. Bad things. Poorly written but not meant to be poorly written. I find it infinitely more entertaining than any story I could ever read in The New Yorker or Harper’s. I don’t know why. The worse the better.”

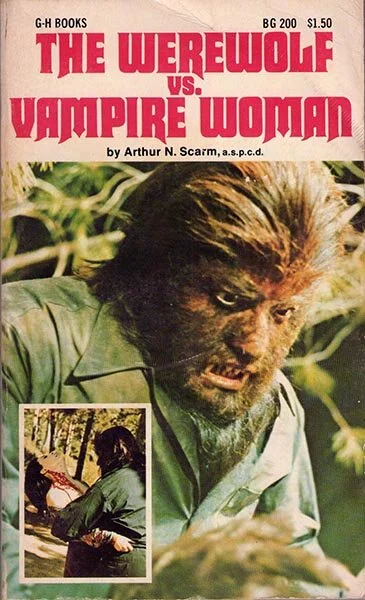

When pushed for an example, Sacks named the 1972 paperback novel, “The Werewolf vs. Vampire Woman,” which he described as “one of the worst ever” books.

“I mean, how could I possibly improve on a line like: ‘Werewolves sure can fuck’? You can’t. It’s perfection.

“I also love the fact that the authors who wrote these types of books weren’t artsy [and] weren’t trying to achieve academic tenure. They were just hustlers out there trying to earn a living. Write a book, move on. No art involved. There’s a type of madness involved. A spark of insanity. I love that.”

Sacks’ original idea was to write a novelization of The Zapruder Film (i.e., the home movie shot by Abraham Zapruder, the man who captured Kennedy’s assassination on film in 1963). Ultimately, Sacks decided it wouldn’t be “commercial” enough to novelize, but added that he still might do it, with the possible plot twist that Kennedy escapes.

The barely remembered drive-in fare of the ’70s that Sacks grew up on inspired him next, and Stinker Lets Loose, a novelization of a purely made-up movie, was set loose in the world. The novelization (actually written by Sacks but credited to one of his many pen names) follows big-rig driver Stinker, his buddy Boner, and his chimp, Rascal, as they race across America to deliver a six-pack of Schlitz to Jimmy Carter in the White House.

The book begins:

Stinker opened his dazzling blue eyes, slowly and with great effort. He could barely see. Was it the middle of the night? No. It felt like daytime. Maybe late morning at the earliest. His eyes squinted from what little light invaded through the dirty, drawn shades.

A languid country song warbled from a radio-alarm clock…It wasn’t a good song, nor did it make much sense, but until the day Stinker died—probably right here in his trailer, crushed under the weight of his vintage erotica collection—he’d be more than okay with it.

Stinker reached across his messy, stained, well-used mattress—over the box of wombat scat and around the jug of doe urine—for the radio’s off button, hit it, and then accidentally knocked over an empty bottle of cinnamon whiskey. The sound of glass hitting and then bouncing along the linoleum floor rang in his ears and made him wince. The label couldn’t be seen, but it was the brand of cheap cooze-booze to be found at any illegal backwoods juke joint owned by a former career Navy cook named Gravy Boat.

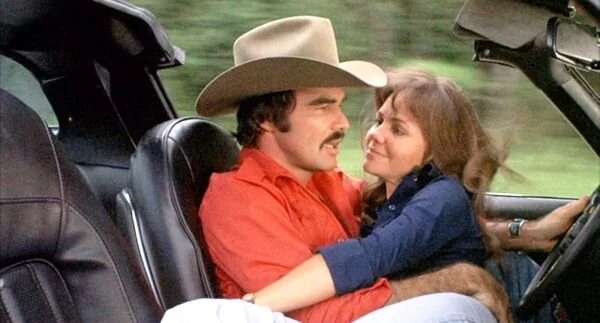

“The CB and trucking movies of the 1970s are very strange,” Sacks said. “I mean, where did they come from? They’re really so Southern and so odd and so of their time. Everything was Southern then, including our President [Carter from Georgia]. All of pop culture seemed to be Southern, which was fine with me. But then a few years later Reagan became President and pop culture moved north and became more urban.”

Watching movies like that now, such as Smokey and the Bandit, is “nostalgic,” Sacks said, but that experience doesn’t always translate for those who didn’t grow up then.

“When I show them to others, especially if they haven’t seen them before, like my daughter, it’s almost like watching sci-fi for them. Who the fuck were these truckers? Why were they considered heroes? They were alcoholics and misogynists and quite possibly racists. Their stories were so simple: Here, take this six-pack of beer and haul it across state lines in 24 hours. That’s it. Just a very simple time. I love that. But it is an odd, extraordinarily specific slice of steaming Americana pie.”

Burt Reynold and Sally Fields filmed four movies together (including Smokey and The Bandit) and dated on-and-off for five years. (Screengrab)

For his next movie novelization, published in 2020, Sacks set his sights on the ’80s and its love affair with John Hughes films focusing on angsty young adults coming-of-age.

In Sacks’ Passable in Pink, credited to a pen name of E.L. Lessert, high schooler Addy Stevenson is hoping for a date to senior prom when she meets rich boy Roland McDough. The novelization includes an insanely detailed cast list for the movie it’s supposedly based on, including such minor yet particular roles as “Heterosexual Student Listening to Jesus Christ Superstar in Red Grand Am” and “Student Who Gives Speech That Wraps Up All The Themes.”

“The ’80s were another interesting time for movies,” Sacks elaborated. “Very capitalistic, very much of the Reagan era. Even the ‘poor’ were ‘rich’ in these movies. That’s one of my problems with John Hughes movies. Even if you lived on the ‘wrong’ side of town, you still looked pretty well off. At least to me. And if you were just ‘average,’ you lived in a mansion.

“Check out the house where Kevin from Home Alone lives. It’s bigger than the goddamn White House.”

Sacks said he grew up on these movies and loved them then but finds them “insufferable” now. He said he wants to slap the characters and mostly identifies with the dads who have to drive the kids to Saturday detention. A recent re-watch of Sixteen Candles with his daughter did not go well.

“Talk about a movie that hasn’t aged gracefully,” he said. “Holy shit. The rape scene. The Asian stereotype. It wasn’t like I had remembered.”

Moving on to the ’90s, Slouchers, also credited to Lessert, follows 22-year-old Willow as she moves to Seattle during the height of the grunge scene. A record store clerk, she documents her listless generation with a digicam, hoping her cinema verité will air on MTV, while torn between her boyfriend, singer Toody, and Mr. Straight, a businessman who likes her.

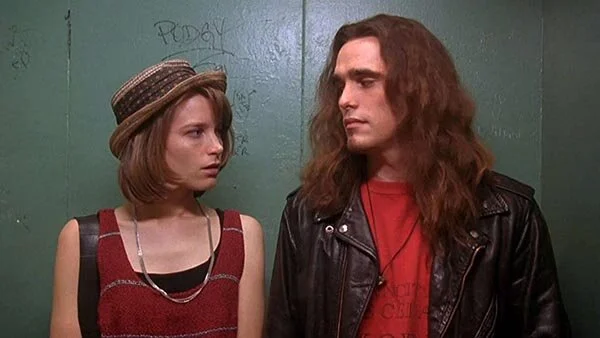

Named “One of Vulture's Top 5 Humor Books of the Year,” Slouchers also has a detailed cast list, including “Clove Cigarette Roller,” “Choreographer to ‘My Sharona’ ” and “Matt Dillon’s Wig Artist.” (“Check out Matt Dillon’s outfit and wig in Singles,” Sacks said. “It’s like looking at a mental patient.”)

“As for the ’90s, I was just coming out of college at that point and I guess you could say I was a ‘slacker.’ If only because I had no job and no social life. I hated the Gen X movies, such as Clerks, Singles, Reality Bites, all of that shit. Just fake and awful.

“They reminded me of the movies that came out in the late 1960s about hippies, written and directed by people in their 50s and 60s. These Gen X movies had no bearing on my own reality. And they’re also very dated.”

Sacks was not a fan of Matt Dillon’s hair in Singles. (Screengrab)

Sacks worked at a record store in the grunge era — he’s not fond of that music either — and said his experience was nothing like what’s depicted in movies like High Fidelity.

“It was an awful time. Those Gen X movies are fantasies. I lived it already and saw the reality. It was a bad place to be and I feared it would never end. Luckily, it did.”

With Slouchers coming out mid-pandemic, Sacks’ promotional efforts are limited but he doesn’t mind. He said he doesn’t like to travel much anyway, and book tours require a lot of money and time just to sell a few copies at signings.

“I’m also pretty lazy and I really do hate the logistics of travel,” he said. “Once I’m there I’m fine. But getting there and back I hate. I suppose it was the same for the Apollo 11 astronauts. And, like them, I am a hero.”

Though movie novelizations are mostly a thing of the past, they aren’t completely gone. The International Association of Movie Tie-In Writers hands out Scribe awards each year for books based on intellectual properties such as Star Trek and Firefly. Continuing a tradition that goes back to the ’30s when King Kong was first published, movie novelizations these days, Vanity Fair notes, “are mainly reserved for science-fiction and fantasy films –– tent poles that translate easily into other media and come with built-in audience interest.”

Though he feels that people are too distracted and not reading as much these days, Sacks hopes the form returns.

“I do know Quentin Tarantino is releasing a new novelization to Once Upon a Time in Hollywood this summer,” Sacks said, “which is really fantastic and I’m excited about that. I thought the movie was brilliant. Can’t wait to read the novelization.”

Simon & Schuster’s Archway Editions will be re-releasing Stinker Lets Loose and Randy in April. Subtitled The Full and Complete Unedited Biography and Memoir of the Amazing Life and Times of Randy S.!, Randy satirizes the proliferation of self-published memoirs by imagining what a “perversely unexceptional” thirtysomething Marylander would write.

“I’m obsessed [with self-published books],” Sacks said. “It’s similar to outsider art, I guess. I just find it a very human, very realistic take on society, who we are and who we want to be. So many failed hopes and dreams laid bare.

“I can find more humanity in one page of a self-published book than in all the pages produced at a typical MFA writing program.”

Though he has a few more ideas for fake novelizations, they’re “on the backburner” for now.

“I don’t want to be known as the guy who ‘writes fake novelizations,’” he said. “Beyond that, I’m writing scripts and audio projects. It’s a terrible time in America but I’m trying to make the best of it.”