Can You Recreate Synesthesia With Music?

A former music journalist gives tips on enhancing your senses, so that sounds have colors, shapes, and textures.

By Erin K Barnes

Synesthesia happens when two or more senses overlap and interact at the same time. (Art: Maria Karambatsakis)

What do Billie Eilish, Leonardo Da Vinci, Jimi Hendrix, and Duke Ellington have in common?

They’ve all been said to have synesthesia.

Although it may sound like a disease where one commits atrocities and then forgets, the condition is actually considered a gift said to have fueled the work of numerous creative geniuses.

The word synesthesia (pronounced “SIN-es-thee-zhuh”) is derived from Greek and means “to perceive together.” Synesthetes’ brains make novel connections between the senses, overlapping them and triggering them at the same time.

People with synesthesia might be able to “hear” colors, “touch” smells, or “taste” textures. Like. A pop song might bloom blue before their eyes like a living painting, or they might associate letters with colors or numbers with human traits.

Most synesthetes' associations are pleasant, non-disruptive, and contribute to a delightfully fantastical way of experiencing the world.

Urban legend has it that Jimi Hendrix named “Purple Haze” because its famous chord, now known as the “Jimi Hendrix” chord, reminded him of a cloudy, violet fog.

It makes sense that synesthesia is linked to music. They’re both acts of connection, bringing together two disparate elements. As synesthesia crosses over from one sense to another (i.e. these sounds are purple), music translates an emotion or a moment in time into the medium of sound (i.e. this is what sadness sounds like).

The difference lies in the fact that whereas abstract creativity can be universal and accessible to many, synesthetes’ connections aren’t. They are repeated, subjective, and for the most part, uncontrollable.

Some people with synesthesia see colors when they hear sounds. (Carl Glover/Flickr)

Figuring out if you have synesthesia…

When I was a music journalist in my twenties, I didn’t know I was wired differently. Writing record reviews was confusing because I kept reporting on things I thought everyone could hear.

The song “All Mirrors” by Angel Olsen, for example, sounds exactly like a sheet of glass to me. I see the song living in an icy, silver room. Olsen's vocals are vertical, like silver slashes of light across a mirror. They echo like the endless blur of reflections when you point two mirrors at each other. The synths are shiny. The beats are crisp like they might shatter the glass.

The hook of the song is "Losing beauty / at least at times it knew me," and at the end, that line is echoed in a lower register like a warped reflection.

To me, it’s as if Olsen took a mirror and translated it directly to sound. This dense visual-sound association is instantaneous for me; I have to deconstruct it to realize I’m even experiencing it.

At age 30, I read an article about people who perceive numbers, letters, and words in color, and discovered I had synesthesia. As far as epiphanies go, however, this one was mundane. I didn’t understand how rare it was until I began telling people about my associations and read the shock on their faces.

I naively thought that everyone saw songs visually, as I do. Some songs look like colors and textures on a canvas in my mind’s eye, while the more reverberant songs ricochet around dark, cavernous rooms. I see melodies in expansive songs, like arena rock songs, carving clouds like jets through a big sky.

So how common is synesthesia?

There are a lot of articles out there about synesthesia. Headlines like “Some People Really Can Taste the Rainbow” revel in the phantasmagorical idiosyncrasies of the synesthete's experience, which is admittedly, a lot of fun. But they can be misleading, making us assume the condition is more rare than it is.

While the percentage of confirmed synesthetes hovers around 4.4%, it might be more common than we think. Research from the University of Michigan suggests that everyone might have it.

As someone who has been doing unofficial research on synesthesia for years, I have to say: duh.

“Synesthesia occurs on a spectrum,” Dr. Jo Shattuck, research faculty at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, explained to me.

For example, most people, she said, will “hear” these silent GIFs.

Dr. Shattuck also happens to be a synesthete herself.

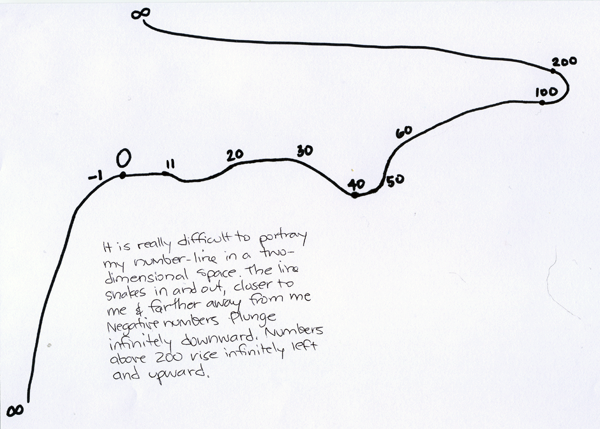

She has “number form” synesthesia, which means that she sees numbers in a constructed 3-D form, strung one-by-one into a helix. The number one is always at her feet, 10 is ankle-level, and 100 just “shoots off into the desert,” she said.

The numbers have always been in the same formation for her, ever since she was a child. She once constructed a visual example of the form the numerals take by using a piece of wire.

How one synesthete sees numbers, aligned in a spatial sequence. (Kelley/Flickr)

It turns out many people with number form synesthesia do this. A quick Google search of the term reveals a fascinating diversity of hand-drawn images: some are spirals, some are mountain ranges, and some are angular plateaus. But each is the formation that synesthetes see numbers arranged into each and every time they think of numbers.

Dr. Shattuck says that in her classes, she often asks her students to give numbers a gender or personality, and that these associations come easily to most.

Once she gets them started, students might declare with great authority that the number 7 is “evil,” that 5 is definitely female, and, taking it even further, that 4 is a “hearty, full-breasted woman.”

The differences between synesthesia and regular old creative thinking

To clarify, the subjective connections of synesthesia are different from the universal, abstract connections we all make.

Why do we consider the word “splash” an onomatopoeia?

Why does it seem like “Gimme Shelter” by the Rolling Stones is always the soundtrack in war films when they’re flying in helicopters?

It's not just Vietnam-era nostalgia; it's because the whirling, chugging rhythm of the song evokes the feeling of flying high and the swirling propellers of a helicopter. It’s this shared metaphorical thinking that most of us either understand inherently or have culturally agreed upon.

In 1929, the concept of collective metaphorical connections was explored by the German-American psychologist Wolfgang Köhler, prompting the study to be successfully replicated many times, even in different languages.

Participants were shown a round shape and a spiky one and asked which should be named ‘Kiki” and which should be named “Bouloba.”

Overwhelmingly, participants paired the word “Kiki” with the spiky shape and “Bouloba” with the round one, proving an important truth about metaphor: Some abstract connections are universal, even across cultures.

Cross-sensory perceptions are ingrained in our culture. Slate reports that marketers use “multi-sensory” approaches to manipulate people into buying their wares: royal blue hues or certain scents might be associated with luxury, for example. These associations may change over time. The color of mint used to be considered warm, and is now associated with cooling in the modern era, according to the Slate article.

Whereas metaphorical thinking fuels creativity and even makes people money, synesthesia is more of a reflex, and might make less artistic sense.

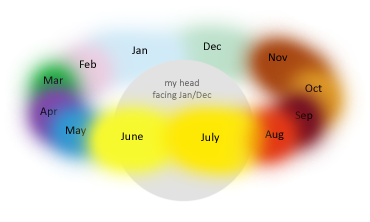

How one synesthete views the yearly calendar in their mind’s eye. (Kelley/Flickr)

In a study from Oxford, synesthetes wrote down their color-alphabet associations, and they were all different, suggesting that there isn’t some universal truth that synesthetes are tapping into.

The question begs, where does metaphorical thinking end and synesthesia begin?

I posed this question to Dr. Shattuck, and, like someone well-acquainted with the complexity of science, she only gave me a broader plane to explore, and not the exact answer I desired.

“What you’re looking for — a definitive answer — well, the truth is more of a grey area,” she said.

“The brain isn’t built for understanding the brain. It’s so complicated that even with the best technology, how we study it is equivalent to poking it with a stick and seeing what happens.”

She then went on to describe the multitudes of receptors our brains use to process the world, and just how specific and different each of their jobs is.

What this mouse trap game of the human senses reveals is just how many opportunities there are for us to process our worlds differently, and how the complex sum of each individual cog can be staggeringly varied.

“The input is the same,” Dr. Shattuck said. She explained that the stimuli that represent our reality are static. For example, the temperature of a bath can be measured with a thermometer, and it stays the same, despite the fact that we’ll all experience that bath differently.

It’s “the output” — the way we individually perceive those sights, sounds and temperatures — that ”is different.”

Synesthesia can be great...if you’re lucky enough to have it

So, how might synesthesia be good for the brain? The Guardian posits that everyone could benefit from it.

“Synesthesia leads to performance enhancements with regards to memory performance and visual mental imagery,” University of Sussex researcher Dr. Nicolas Rothen explained to the Guardian.

Just imagine when numbers are paired with colors, how much easier they would be to remember. Associations act like markers in the brain.

That’s why people who participate in the World Memory Championships — an organized sport that involves memorizing loads of information while being timed — use techniques from synesthesia to practice.

Like a trusty acid trip when you need a shift in perspective, connecting different parts of your brain can lead to personal and creative epiphanies.

Our brains and bodies crave sensory input to make us feel balanced. Modern occupational therapists use a practice called “sensory integration” to treat everything from autism to toddler meltdowns to anxiety and depression.

Exploring my synesthesia has had a profound effect on me.

Listening to music with headphones on and writing down my associations makes me feel happy, even manic. It has also fueled a burst of creativity that has led me to write a memoir in a week and three books in a few years, one of which comes out in May.

So can you replicate synesthesia if you don’t already have it?

There are numerous studies that set out to teach non-synesthetes how to experience synesthesia on their own. University of Michigan psychologists played sounds in a dark room, and half of their participants saw flashes of light in conjunction with the sounds (when no light was there).

Scientists at the University of Amsterdam had subjects read books with colors in order to build the color-word associations, and subjects began to see colors on their own when reading.

The academic consensus is that there are 60 to 150 identified types of synesthesia, and they range from lexical-gustatory synesthesia, when words and syllables have tastes, to the personification of letters, numbers, or objects.

Some synesthetes may even develop erotic feelings towards inanimate objects through “object personification” synesthesia.

Out of all the types of synesthesia I seem to experience — mirror touch synesthesia, grapheme-color synesthesia, and chromesthesia — my associations with music are by far the most pleasurable.

The guitar solo from Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven” is circular, glossy, tan, and tinged with maroon. It tastes like clay and it’s so cool, it almost burns my mouth.

The Raveonettes’ cover of “I Wanna Be Adored” crunches like aluminum foil in my head.

“Strangers” by Psychic Twin feels like a rainbow-colored pixie is running in stilettos all over my body.

And you’ll have to read my memoirs to learn the profound reaction Air’s Walkie Talkie has upon me.

Because of these sensory indulgences, I find myself replaying songs like an addict chasing the dragon.

How you can learn to taste your own sweet guitar solos

To see if I could teach others how to have similar associations when listening to music, I created a guide that is published below. It’s by no means scientific in nature, consisting entirely of tips I came up with on my own.

But, two neuroscientists did approve this article before it was published and said that while it was by no means a rigorous study, it was a cool experiment.

Because music is the key that unlocks my synesthesia, my step-by-step guide involves having access to Spotify, where I’ve neurotically catalogued the shapes, textures, sensations, movement, and colors that certain songs evoke for me into copious playlists. For example, one playlist is filled with songs that make me feel achy and another is devoted to songs that look iridescent to me.

Your practice will involve listening to music for half-hour chunks as often as you’d like. I strongly recommend using headphones.

Sit alone in a comfortable position, with no distractions, preferably in the dark — and get ready to really listen.

The Playlists:

Shapes: round, square, triangle, lines, curly, chevron, chunky

Textures/Sensations: watery, smoke, pointillism, dusty, glass shards, mahogany, airy, achy, ribbed, velvet, smudged, glitz, blurred, lush, warm

Colors: silver, iridescent, rainbow, crimson, blue light on black, burgundy

Objects: floral arrangement, gold stars, water droplets, sunlight, neon bar sign

The Process:

1. Start with one focus

Select one attribute to start (“Shapes,” “Textures/sensations,” “Movement,” “Colors,” or “Objects”) and listen to the playlists within that category, observing the differences in sounds.

For your first session, I recommend starting with “Shapes” or “Textures/sensations” because my other associations (like “Color”) might be more subjective.

If you can’t hear the quality the playlist you’re listening to is named after — say if certain songs don’t sound “square” to you — try switching between the divergent playlists to highlight the contrasting sounds.

2. Listen and analyze what you’re hearing

As you play the songs, either close your eyes or soften your gaze, and imagine the shape or sensation you’re listening to. Some shapes and textures you might hear right away, and others might be waiting in the chorus.

Think about what makes certain songs sound “round.” Is it the soft drum beat? A lot of “o” sounds? What makes the “square” songs angular? What makes the “glass shards” songs sound jagged? Are the “lines” songs just songs with a standout melody? Can you imagine the melody written out like lines, going up and down your visual canvas? Can you hear where the guitars “smudge”?

Write down your own associations and try to pinpoint the reason(s) why you came up with them.

Listen to the “airy” playlist and imagine you’re outdoors. Listen for the sonic wavering in the “iridescent” songs and imagine the color spectrum bending. Feel the temperature rise when you listen to the “warm” playlist and try to determine how it differs from the “sunlight” playlist (hint: the latter is a bit cooler and more visually bright, to me). Feel millions of pricks tingling your skin as you listen to the “pointillism” playlist. Imagine you’re underwater as you listen to the “watery” playlist or just listen to it in the tub.

Maybe your associations will be different from mine. I actually hope they are. If you have different associations, write them down!

3. Create your own connections

At whatever point you begin to “see” some of my associations, you are ready to discover or create your own.

Sit down with your own music and hit “shuffle.” Try to imagine the song like a painting, the notes like brushstrokes. Are they fluttery, sharp, soft, hard, sleek, heavy? What is the background of the song? Does it exist in a large dark room, on a sunny warm stoop, in outer space? What colors do you see? Does it remind you of a smell or shape?

If you find yourself stuck, you may skip to the next song, it’s okay. This is not a test.

I find that certain genres of music aren’t as textured or colorful for my synesthesia, like country, folk, and punk. I struggle to “see” any songs by Bob Dylan, which might be why I have a controversial distaste for his music.

Cycle through until you can make an association. If you’re not making any, force yourself to choose.

Remember, the more connections you make in your brain, the more you’ll open up to exponentially new creative experiences. In other words, if it feels weird or doesn’t “work” on the first try, don’t give up. This is a skill that takes time to hone.

Happy synesthesiating!