Inside the World of Velvet Nude Paintings

Better than a poster or a magazine spread, and almost as good as the real thing.

By Jessie Schiewe

Credit: Velveteria

She’s standing there, looking back at you, her head swiveled over her right shoulder.

The woman’s gaze is pleasant if not pleading — her eyebrows arched, lips a fiery coral red. Her posture is impeccable. Her stomach is sucked in.

And, but for a single, gossamer shawl, she’s entirely nude.

Not that the shawl is hiding much of her.

It hangs below her butt, emphasizing but not blocking it, just like a copyeditor underlining a word. Based on her pose, based on the bright beam of light shining down on her from behind, illuminating the small of her back and then her ass and then the sheltered groove below it, it’s clear she wants to be looked at.

And not just that part of her, all parts of her. The shadows pooled between her shoulder blades, the gradual incline of her right breast, a nipple, but just the tip.

If you stare long enough, it’s easy to forget she’s just a velvet painting.

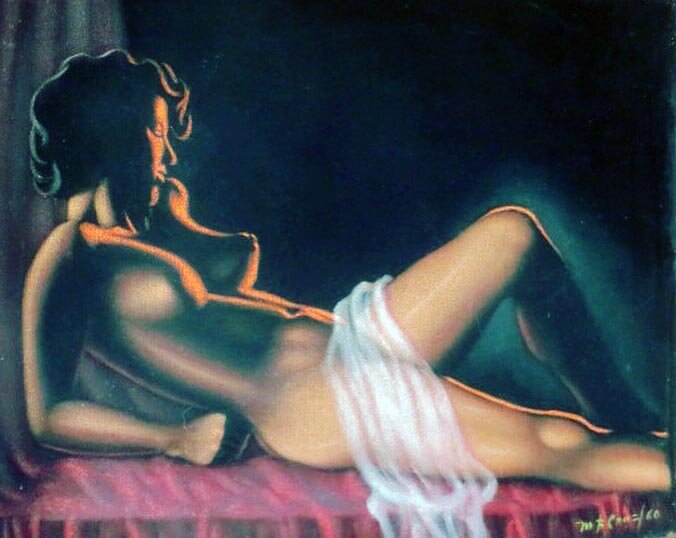

A velvet nude painted in the Philippines that Andersen and Baldwin own. (Velveteria)

Elvis. That’s probably the first thing that comes to mind when you think of velvet paintings. Then maybe clowns, black panthers, Jesus, his mom, or dogs playing poker.

But don’t forget the nudes. They, too, were a popular motif amongst velvet painters. Easy to titillate and quick to sell, they toed the line between fine art and plain old smut.

“People loved them. They went ape for them,” explained Caren Andersen, an expert on velvet art and a longtime collector of the works.

“Now there are still people who wouldn’t have one in their house to save their life, but there are other people that are really fascinated by them, too.”

Together, with her business partner Carl Baldwin, she’s been collecting velvet paintings for decades. And not just of nudes, but of all subjects. In 2005, the pair founded Velveteria, one of the first museums dedicated solely to velvet art, in Portland, Oregon. A few years after that, they published a hardcover coffee table book of their collection through Chronicle Books, and they lent some of their works to Portland’s famed Powell’s Books for a showcase. The museum moved to Los Angeles’ Chinatown neighborhood in 2013, but closed in September 2019 due to financial constraints.

But though the public can no longer view them, Anderson and Baldwin still maintain their vast collection of velvet art. They think it includes about 2,000 or 3,000 paintings, but they don’t know for sure because no one’s ever taken an exact inventory. Of those, a couple hundred are of naked ladies.

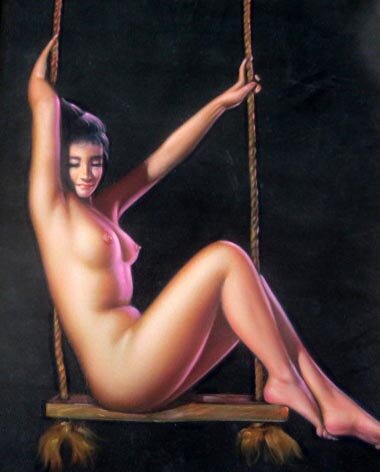

One of the velvet nudes in Andersen and Baldwin’s collection. (Velveteria)

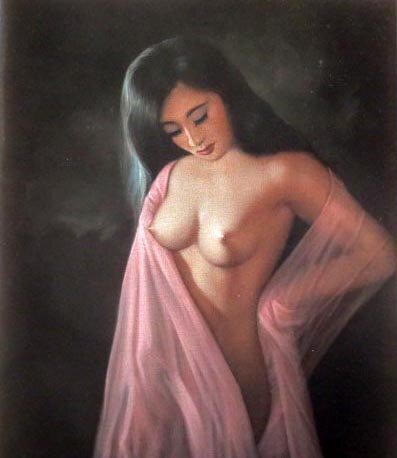

Their velvet nudes are an eclectic assortment, featuring blondes and brunettes in various shapes, skin tones, and nipple sizes. The women might be standing or sitting, their legs tucked underneath them or hanging from a swing, their hands hanging at their sides or clasped behind their backs or adjusting their hair.

The painted ladies are all naked, but what they choose to reveal, and how much, differs. Some show only their backsides; others, just their chests. A strategically placed prop, like a fish bowl, might shield one body part, while an un-sashed robe might reveal something else.

There are full-frontal nudes, too, ones that are candid and commanding of attention, that don’t try to hide anything at all. Sometimes they’re made even more realistic by the canvases they’re painted on; standing at an almost life-like height of 5-feet tall.

These days, Anderson and Baldwin have slowed down with their velvet nude purchases, having spent the last few decades stocking up.

A velvet nude painting created by an artist from Okinawa, Japan, that Anderson and Baldwin purchased for $92 in Oregon. (Velveteria)

“We used to go nuts looking for them. We used to go crazy. It was insane,” Anderson told OK Whatever.

She recalled spending as much as $300 on one velvet nude painting at a San Francisco swap meet in 2001. Another, purchased for $92 at an antique store in Eugene, Oregon just before closing, likely belonged to a professor before it came into their ownership.

The pair have also purchased whole collections from people — because yes, apparently there are others out there who hoard velvet nude paintings.

They’ve had a few donated, too.

One time, when Velveteria was still open, an older woman in her 60s or 70s came into the museum with a velvet nude painting that had been hanging above her and her husband’s bed since they married. Now that he’d passed away, she was ready to part with it, and wanted Anderson and Baldwin to have it.

“We were just flabbergasted,” Anderson said.

Most if not all velvet nude paintings were made decades ago, predominantly in the 1960s and 1970s. According to Anderson, the vast majority were made by artists in Mexico and sold in border towns like Tijuana, Juarez, and Nogales.

“People went down there just for them,” she said. “In those days, you could go down to Mexico easy, go down for the day, and get your velvet paintings and your bullwhips and God knows what else.”

The Philippines was also a hotspot of velvet painting action. As the craft gained steam in the 1970s, artists began to emerge elsewhere, too, particularly in the Pacific Islands and Japan.

A velvet nude by Cece Rodriguez, who is believed to still be alive today. (Velveteria)

As far as Anderson and Baldwin know, only one painter from velvet art’s heyday is still alive today: Cece Rodriguez, one of the scene’s sole females, who, today, must be around 99 years old.

The vast majority of velvet nudes were painted using spreads from Playboy magazines, Anderson said. The artists were usually short on time and didn’t have the liberty of using a studio or access to a live model, so copying the models in Playboy was the next best thing.

“I think they did them quickly, just to make some money,” Anderson mused. “Also, Playboy started in ‘53, when Carl and I were born, which we both think is kind of interesting.”

Velvet nudes also give you an idea of what the beauty standards were back when they were painted. From the women’s hairdos to their waist sizes, they’re reflections of society’s past tastes. Emphasis was routinely placed on the breasts — through subtle shades of light or particularly angled poses — more so than on their butts, which don’t feature as regularly in velvet nude works.

“The bodies were usually pretty curvaceous and not super skinny,” Andersen said. “They look great, but they definitely weren’t waifs. They wanted big-busted women.”

It also wasn’t uncommon for the artist to tweak the women ever so slightly so that they look more like them. In most cases, this was likely not a conscious move on the artist’s part, but more of a natural inclination to paint what one knows best. After years of collecting velvet nudes, Andersen has a keen eye for spotting these discrepancies, noticing when a woman’s body and pose resembles a Playboy pin-up, yet she has a face that looks slightly more Latina or Asian than Anglo.

“A lot of painters do it. I do it, too, and I’m a painter. Because sometimes, when I paint something, it’ll look a little like me and I didn’t even mean for it, but that kind of happens,” she said. “So it made sense that what the painters would paint would end up looking a little more like them.”

Sometimes, velvet nude artists would intentionally paint people they knew onto the faces of the women they were creating.

A velvet nude by Charles McPhee. (Velveteria)

Charles McPhee, a velvet nude painter from New Zealand whose works now sell for a couple thousand dollars, used to do this a lot.

He’d slap his wife’s face onto the bodies of Playboy models, which for Andersen was always a dead giveaway because “his wife was Tahitian and [some of his women] didn’t have Tahitian nipples.”

There were some artists who used actual real, live models to paint their velvet nudes, too.

In the post World War II era, a painter and former U.S. Marine named Ralph Burke Tyree relocated to the Pacific, living in Hawaii, Samoa, and Guam, where he’d paint velvet nudes using large format photographs he’d taken of actual models.

Background imagery in velvet nude paintings is often absent, with most artists content to just leave the women floating in a black void.

But some artists, such as the Hawaii-based Bill Erwin — who was a student of another famed velvet painter, Edgar Leeteg — did put in the time and effort to paint scenery in their works. His nudes, which are now worth more than $1,000, would feature rock formations, gnarled tree trunks, waterfalls, or full-on villages behind the posed women.

It wasn’t just time and a lack of resources that led most velvet nude painters to omit background imagery. It’s also just hard to do.

Velvet artist Bill Erwin was known for adding in backgrounds on his paintings. (Velveteria)

Painting is already a difficult skill to master, and when you pair it with velvet canvases, the ordeal becomes even more challenging. Because the artists worked with oil paints, if they made one mistake, they were done for and would have to throw out the canvas and start again.

And for many of them, simply executing the nude woman perfectly the first time was enough to qualify it as being “done” without having to add in the extra challenge of creating background imagery.

Velvet is a tricky fabric to work with, one whose difficulty level is occasionally equated to that of glasswork or woodwork — art-forms that are not forgiving if errors are made.

“Once you put the paint on the canvas, you’re sort of stuck with it,” Anderson explained. “Like, if you put the nose in the wrong place, you might as well throw it out. It’s not like regular painting on canvas where you can keep going over it and over it if you make a mistake.”

So if the fabric is so challenging to paint on, why work with it in the first place?

Just look at a velvet painting and you’ll have the answer.

When executed properly, images on velvet seem to glow in ways that are different than how they would on regular canvases. There’s a luminescence about them, a crisp three-dimensional look that makes the figures appear almost as if they might jump right off the campus and come to life.

And, when you’re gazing at a velvet nude, isn’t that exactly what you’d want?

A pop-up museum in Los Angeles tried to find the answer.