Modern-Day Hermits: Mauro in Italy

For 30 years, he’s been the only resident on a small Italian island. Now, local authorities want to evict the 80-year-old, putting an end to his reclusive lifestyle.

By Jessie Schiewe

“Modern-Day Hermits” is an ongoing series about the rare and fascinating people who’ve chosen solitude over everything else. Read more of the series here.

When Mauro Morandi first arrived on the pink, sandy shores of Budelli, it was an accident. Then 50 years old, the Italian had been trying to sail to Polynesia when his catamaran broke down by the small island that lies between Sardinia and Corsica.

This was in July of 1989 during a time when Morandi — a longtime nonconformist who used to run away from home as a kid and participate in political rallies — was trying to extricate himself from “a society that does not take the individual into account, but thinks only of power and money,” he told CNN. Remaining on the deserted island whose shores he washed up on seemed like the perfect out.

Thirty years later and Morandi, who previously worked as a school P.E. teacher, now lives in a tumbledown shack with two cats and a hen. For power, he relies on solar panels, and he quenches his thirst with rainwater collected and purified through a homemade system. Swim trunks are his daily uniform.

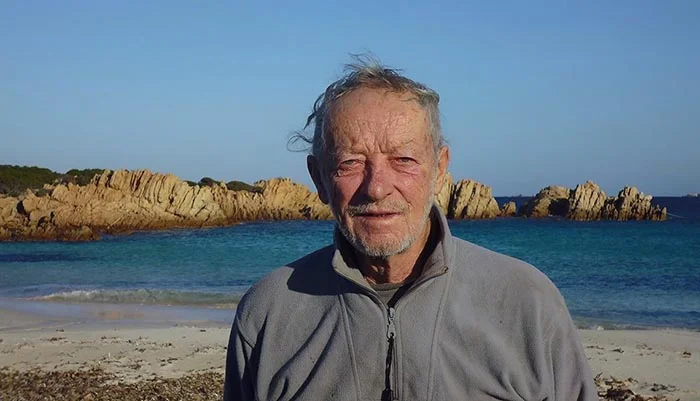

Mauro Morandi has been living on the small Italian island of Budelli since 1989. (Facebook)

Through a stroke of luck, Morandi’s arrival on Budelli coincided with the departure of the island’s previous caretaker, who was about to retire. They arranged for the Italian to take his place, allowing him to legally remain there and giving him a sense of purpose, to boot. For the last three decades, he’s been Budelli’s official guardian, maintaining the upkeep of the archipelago and monitoring the shores of La Spiagga Rosa, the island’s most famous pink sand beach which has been cordoned off since the 1990s.

Daytrippers often stop by to explore the island and meet Morandi, who, when he first moved to the island, had no interest in communicating with them.

“The first few years I was very standoffish," Morandi told CNN. "I did not want to communicate with anyone who came to see the pink beach, and I enjoyed all this beauty alone.”

Now when Budelli gets visitors, the modern-day hermit looks forward to engaging with them, giving tours and talks in the summer months.

Ownership of the island has changed hands multiple times over the years, most recently in 2016 when it became a government-owned national park. Wi-Fi has since been installed on Budelli, which has been a boon for lost tourists, as well as Morandi.

He now spends his time photographing the island’s remote and secluded landscape using a smartphone someone brought to him. He shares his snaps on his Instagram account — @maurodabudelli, or, “Mauro of Budelli,” — where he has amassed more than 20,000 followers in three years. He also has Facebook and Twitter accounts, and uses his geolocation to post his photos on Google Maps.

In 2018, despite only having a tablet to work on, Morandi also published a digital memoir through Amazon Kindle about his time spent on the island.

“I could only feel waves lapping, insects buzzing, birds tweeting, and some raspy seagull shouting,” he wrote in it. “Not a human voice, nor noise of engines. No loud music but the intimate music of the wild and uncontaminated nature only.”

Morandi says he only wants the best for Budelli, but his right to live there has been challenged in recent years. The island’s incorporation into the national parks system has made the Italian’s role as custodian obsolete, with local authorities describing his presence as “incompatible” for such a protected area.

Morandi has purportedly been asked to leave Budelli on multiple occasions and received threats about plans to demolish his shack if he doesn’t.

“In recent years, several structures have been built illegally on the island and we have a duty to clear them away,” Fabrizio Fonnesu, a national parks employee, told the Italian-centric Australian publication, Il Globo.

Others don’t want to see the modern hermit go. When he was first asked to leave in 2016, a petition was circulated that received more than 18,000 signatures. It has helped bolster his existence on the island in the years since, but nothing is certain. For now, Morandi’s fate remains in limbo.

Why British model Becky Holt doesn’t regret inking her forehead.